New DNA tests on a victim’s shawl matches killer’s semen to a living relative of Kosminski

Forensic scientists claim to have finally identified the real Jack the Ripper, the infamous serial killer who terrorised the streets of London over a century ago.

The results of genetic tests published this week suggest a Polish jewish immigrant, barber Aaron Kosminski, 23, a prime police suspect at the time, was really a demon barber responsible for the horrific murders.

Kosminski was said to be suffering from paranoid schizophrenia with one theory suggesting he may have had an unquenchable thirst for jewish ritual slaughter using women as a human sacrifice.

Forensic examination of a blood-speckled silk shawl said to have been found next to the mutilated body of Catherine Eddowes, the killer’s fourth victim, in 1888, provided the evidence. The shawl has speckles of what is said to be DNA traces from the victim and killer in the form of blood and semen.

Over three months another four women were also murdered in Victorian London and the killer was never caught.

This isn’t the first time Kosminski has been linked to the crimes. But it is the first time the supporting DNA evidence has been published in a peer-reviewed journal. However, critics say the evidence isn’t strong enough to declare this case closed. They also point out the “canonical five” killings, that are most frequently blamed on the Ripper, concluded in 1888; Kosminski’s movements were not restricted until 1891 when he was he was transferred to Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum on February 7. Why did he not kill during those three years?

The first genetic tests on shawl samples were conducted several years ago by Jari Louhelainen, a biochemist at Liverpool John Moores University in the UK, but he said he wanted to wait for the fuss to die down before he submitted the results, reports Science Magazine.

Author Russell Edwards, who bought the shawl in 2007 and gave it to Louhelainen, used the unpublished results of the tests to identify Kosminski as the murderer in a 2014 book called Naming Jack the Ripper. But geneticists complained at the time that it was impossible to assess the claims because few technical details about the analysis of genetic samples from the shawl were available.

The new paper lays those out, up to a point. In what Louhelainen and his colleague David Miller, a reproduction and sperm expert at the University of Leeds in the United Kingdom, claim is “the most systematic and most advanced genetic analysis to date regarding the Jack the Ripper murders,” they describe extracting and amplifying the DNA from the shawl. The tests compared fragments of mitochondrial DNA—the portion of DNA inherited only from one’s mother—retrieved from the shawl with samples taken from living descendants of Eddowes and Kosminski. The DNA matches that of a living relative of Kosminki, they conclude in the Journal of Forensic Sciences.

The analysis also suggests the killer had brown hair and brown eyes, which agrees with the evidence from an eyewitness. “These characteristics are surely not unique,” the authors admit in their paper. But blue eyes are now more common than brown in England, the researchers note.

The results are unlikely to satisfy critics. Key details on the specific genetic variants identified and compared between DNA samples are not included in the paper. Instead, the authors represent them in a graphic with a series of coloured boxes. Where the boxes overlap, they say, the shawl and modern DNA sequences matched.

The authors say in their paper that the Data Protection Act, a U.K. law designed to protect the privacy of individuals, stops them from publishing the genetic sequences of the living relatives of Eddowes and Kosminski. The graphic in the paper, they say, is easier for nonscientists to understand, especially “those interested in true crime.”

Walther Parson, a forensic scientist at the Institute of Legal Medicine at Innsbruck Medical University in Austria, says mitochondrial DNA sequences pose no risk to privacy and the authors should have included them in the paper. “Otherwise the reader cannot judge the result. I wonder where science and research are going when we start to avoid showing results but instead present colored boxes.”

Hansi Weissensteiner, an expert in mitochondrial DNA also at Innsbruck, also takes issue with the mitochondrial DNA analysis, which he says can only reliably show that people—or two DNA samples—are not related. “Based on mitochondrial DNA one can only exclude a suspect.” In other words, the mitochondrial DNA from the shawl could be from Kosminski, but it could probably also have come from thousands who lived in London at the time.

Other critics of the Kosminsky theory have pointed out that there’s no evidence the shawl was ever at the crime scene. It also could have become contaminated over the years, they say.

The new tests are not the first attempt to identify Jack the Ripper from DNA. Several years ago, U.S. crime author Patricia Cornwell asked other scientists to analyze any DNA in samples taken from letters supposedly sent by the serial killer to police. Based on that DNA analysis and other clues she said the killer was the painter Walter Sickert, though many experts believe those letters to be fake. Another genetic analysis of the letters claimed the murderer could have been a woman.

The life and death of Aaron Kosminski

Aaron Kosminski was born in Klodawa in Congress Poland, then part of the Russian Empire. His parents were Abram Józef Kozmiński, a tailor, and his wife Golda née Lubnowska. He may have been employed in a hospital as a hairdresser or orderly for a time. Aaron emigrated from Poland in 1880 or 1881, likely with his sisters’ families. The family initially lived in Germany for a while. A nephew of Aaron’s was born there in 1880 and a niece in 1881. It is not known precisely when Aaron left Poland to join his sisters or whether he lived in Germany for any length of time, although he may have left Poland as a result of the April 1881 pogroms following the assassination of Tzar Alexander II, the impetus for many other Jews to emigrate. The family moved to Britain and settled in London sometime in 1881 or 1882. His mother, who was listed as a widow, apparently did not emigrate with the family immediately, but had joined them by 1894. It is unknown whether his father died or abandoned the family, but he did not emigrate to Britain with the rest of them. It is known that he had likely died before 1901, and an 1887 death certificate indicates that an Abram Kosminski had died in the Polish town of Kolo, only five miles from Grzegorzew, the hometown of Kosminski’s father.

In London, Kosminski embarked on a career as a barber in Whitechapel, an impoverished slum in London’s East End that had become home to many Jewish refugees who were fleeing economic hardship in eastern Europe and pogroms in Tsarist Russia. However, he may have worked only sporadically: it was reported that he had “not attempted any kind of work for years” by 1891. He possibly relied on his sisters’ families for financial support, and may have lived with them at 3 Sion Square in 1890 and 16 Greenfield Street in 1891, indicating that his sisters possibly shared responsibility for caring for him and he alternated living between their family homes.

On 12 July 1890, Kosminski was placed in Mile End Old Town workhouse because of his insane behaviour, with his brother Woolf certifying the entry, and was released three days later. On 4 February 1891, he was returned to the workhouse, possibly by the police, and on 7 February, he was transferred to Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum. A witness to the certification of his entry, recorded as Jacob Cohen, gave some basic background information and stated that Kosminski had threatened his sister with a knife. It is unclear whether this meant Kosminski’s sister or Cohen’s. Kosminski remained at the Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum for the next three years until he was admitted on 19 April 1894 to Leavesden Asylum. Case notes indicate that Kosminski had been ill since at least 1885. His insanity took the form of auditory hallucinations, a paranoid fear of being fed by other people that drove him to pick up and eat food dropped as litter, and a refusal to wash or bathe. The cause of his insanity was recorded as “self-abuse”, which is thought to be a euphemism for masturbation. His poor diet seems to have kept him in an emaciated state for years; his low weight was recorded in the asylum case notes. By February 1919, he weighed just 96 pounds (44 kg). He died the following month, aged 53.

Could it be Kosminski?

Between 1888 and 1891, the deaths of eleven women in or around the Whitechapel were linked together in a single police investigation known as the “Whitchapel murders”. Seven of the victims suffered a slash to the throat, and in four cases the bodies were mutilated after death. Five of the cases, between August and November 1888, show such marked similarities that they are generally agreed to be the work of a single serial killer, known as “Jack the Ripper”. Despite an extensive police investigation, the Ripper was never identified and the crimes remained unsolved. Years after the end of the murders, documents were discovered that revealed the suspicions of police officials against a man called “Kosminski”.

An 1894 memorandum written by Sir Melville MacNaughten, the Assistant Chief Constable of the London Met Police, names one of the suspects as a Polish Jew called “Kosminski” (without a forename). Macnaghten’s memo was discovered in the private papers of his daughter, Lady Aberconway, by television journalist Dan Farson in 1959, and an abridged version from the archives of the Metropolitan Police was released to the public in the 1970s. Macnaghten stated that there were strong reasons for suspecting “Kosminski” because he “had a great hatred of women … with strong homicidal tendencies”.

In 1910, Assistant Commissioner Sir Robert Anderson claimed in his memoirs The Lighter Side of My Official Life that the Ripper was a “low-class Polish Jew”. Chief Inspector Donald Swanson, who led the Ripper investigation, named the man as “Kosminski” in notes handwritten in the margin of his presentation copy of Anderson’s memoirs. He added that “Kosminski” had been watched at his brother’s home in Whitechapel by the police, that he was taken with his hands tied behind his back to the workhouse and then to Colney Hatch Asylum, and that he died shortly after. (Whereas Aaron Kosminski did not die until 1919). The copy of Anderson’s memoirs containing the handwritten notes by Swanson was donated by his descendants to Scotland Yard’s Crime Museum in 2006.

In 1987, Ripper author Martin Fido searched asylum records for any inmates called Kosminski, and found only one: Aaron Kosminski. At the time of the murders, Aaron apparently lived either on Providence Street or Greenfield Street, both of which addresses are close to the sites of the murders. The addresses given in the asylum records are in Mile End Old Town, just on the edge of Whitechapel. The description of Aaron’s symptoms in the case notes indicates that he had paranoid schizophrenia, like other known serial killers. Macnaghten’s notes say that “Kosminski” indulged in “solitary vices”, and in his memoirs Anderson wrote of his suspect’s “unmentionable vices”, both of which may match the claim in the case notes that Aaron committed “self-abuse”. Swanson’s notes match the known details of Aaron’s life in that he reported that the suspect went to the workhouse and then to Colney Hatch, but the last detail about his early death does not match Aaron, who lived until 1919.

Anderson claimed that the Ripper had been identified by the “only person who had ever had a good view of the murderer”, but that no prosecution was possible because both the witness and the culprit were Jews, and Jews were not willing to offer testimony against fellow Jews. Swanson’s notes state that “Kosminski” was identified at “the Seaside Home”, which was the Police Convalescent Home in Brighton. Some authors express scepticism that this identification ever happened, while others use it as evidence for their theories. For example, Donald Rumbelow thought the story unlikely, but fellow Ripper authors Martin Fido and Paul Begg thought there was another witness, perhaps Israel Schwartz, Joseph Lawende, or a policeman. In his memorandum, however, Macnaghten stated that “no-one ever saw the Whitechapel murderer”, which directly contradicts Anderson’s and Swanson’s recollection. Sir Henry Smith, Acting Commissioner of the City of Lodnon Police at the time of the murders, scathingly dismissed Anderson’s claim that Jews would not testify against one another in his own memoirs written later in the same year, calling it a “reckless accusation” against Jews. Edmund Reid, the initial inspector in charge of the investigation, also challenged Anderson’s opinion. There is no record of Aaron Kosminski in any surviving official police documents except Macnaghten’s memo.

In Kosminski’s defence, he was described as harmless in the asylum. He had originally been taken into custody for threatening either his sister or the sister of a witness to his admittance with a knife, and brandished a chair at an asylum attendant in January 1892, but these two incidents are the only known indications of violent behaviour. In the asylum, Kosminski preferred to speak his native language, Yiddish, which indicates that his English may have been poor, and that he was unable to persuade English-speaking victims into dark alleyways, as the Ripper was supposed to do. The “canonical five” killings that are most frequently blamed on the Ripper concluded in 1888; Kosminski’s movements were not restricted until 1891.

The Jack the Ripper story

Jack the Ripper was a previously unidentified serial killer generally believed to have been active in the largely impoverished areas in and around the Whitechapel district of London in 1888. In both the criminal case files and contemporary journalistic accounts, the killer was called the Whitechapel Murderer and Leather Apron.

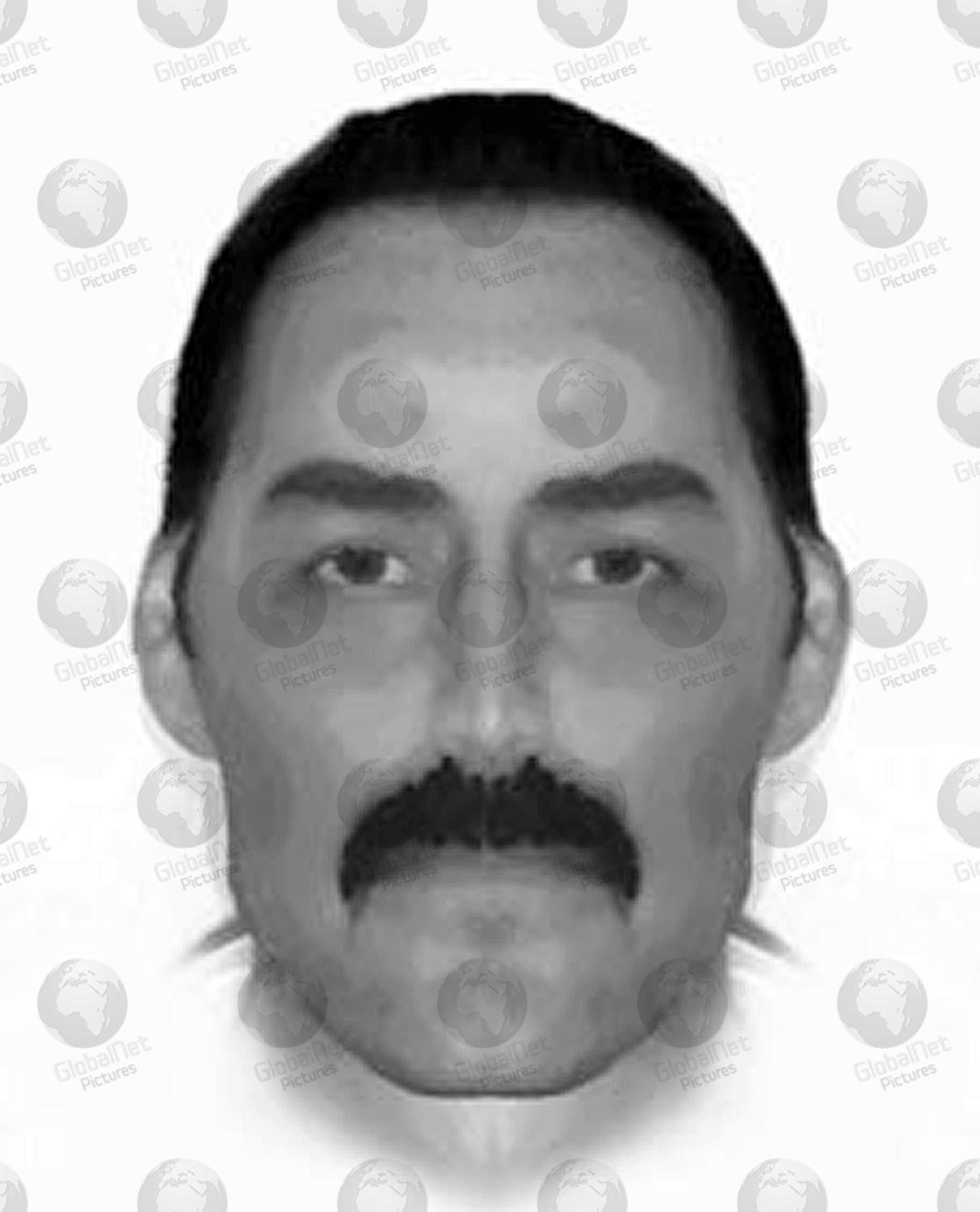

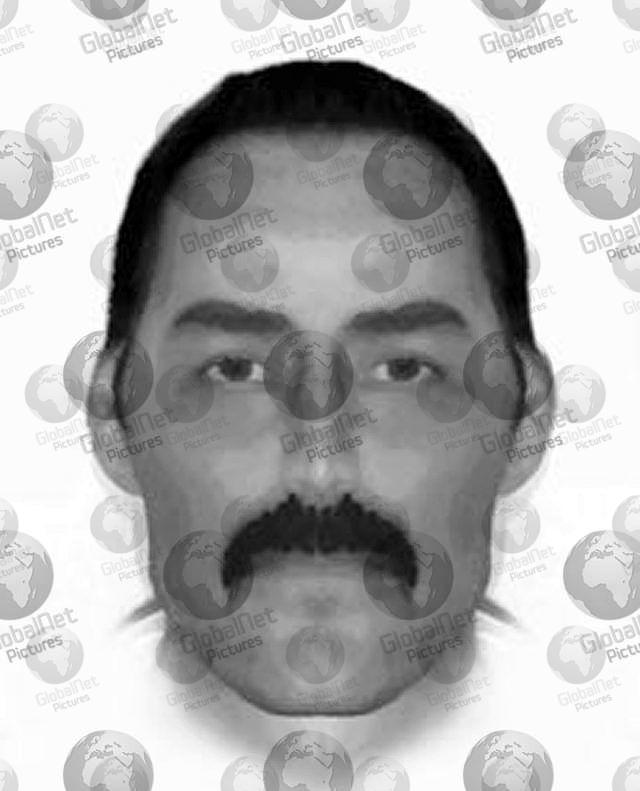

State of the art photofit of Jack the Ripper created by Scotland Yard’s violent crime command in 2006. It was compiled after studying evidence from the ripper case files from well over a century ago. Police then used modern policing techniques to compose the portrait and aged him at between 25 and 35, with a height between 5ft 5ins and 5ft 7ins tall and described him as stocky. At the time the police claimed the techniques used could even pinpoint his home address

Attacks ascribed to Jack the Ripper typically involved female prostitutes who lived and worked in the slums in the East end of London whose throats were cut prior to abdominal mutilations. The removal of internal organs from at least three of the victims led to proposals that their killer had some anatomical or surgical knowledge. Rumours that the murders were connected intensified in September and October 1888, and letters were received by media outlets and Scotland Yard from a writer or writers purporting to be the murderer.

The name “Jack the Ripper” originated in a letter written by someone claiming to be the murderer that was disseminated in the media. The letter is widely believed to have been a hoax and may have been written by journalists in an attempt to heighten interest in the story and increase their newspapers’ circulation. The “From Hell” letter received by George Lusk of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee came with half of a preserved human kidney, purportedly taken from one of the victims. The public came increasingly to believe in a single serial killer known as “Jack the Ripper”, mainly because of the extraordinarily brutal nature of the murders, and because of media treatment of the events.

Extensive newspaper coverage bestowed widespread and enduring international notoriety on the Ripper, and the legend solidified. A police investigation into a series of eleven brutal killings in Whitechapel up to 1891 was unable to connect all the killings conclusively to the murders of 1888. Five victims— Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly—are known as the “canonical five” and their murders between 31 August and 9 November 1888 are often considered the most likely to be linked. The murders were never solved, and the legends surrounding them became a combination of genuine historical research, folklore, and pseudohistory. The term “ripperology” was coined to describe the study and analysis of the Ripper cases. There are now over one hundred hypotheses about the Ripper’s identity, and the murders have inspired many works of fiction.

Background

In the mid-19th century, Britain experienced an influx of Irish immigrants who swelled the populations of the major cities, including the East End of London. From 1882, Jewish refugees from pogroms in Tsarist Russia and other areas of Eastern Europe emigrated into the same area. The parish of Whitechapel in London’s East End became increasingly overcrowded. Work and housing conditions worsened, and a significant economic underclass developed. Robbery, violence, and alcohol dependency were commonplace, and the endemic poverty drove many women to prostitution. In October 1888, London’s Metropolitan Police Service estimated that there were 62 brothels and 1,200 women working as prostitutes in Whitechapel. The economic problems were accompanied by a steady rise in social tensions. Between 1886 and 1889, frequent demonstrations led to police intervention and public unrest, such as that of 13 November 1887. Anti-semitism, crime, nativism, racism, social disturbance, and severe deprivation influenced public perceptions that Whitechapel was a notorious den of immorality. In 1888, such perceptions were strengthened when a series of vicious and grotesque murders attributed to “Jack the Ripper” received unprecedented coverage in the media.

The Whitechapel murders

The large number of attacks against women in the East End during this time adds uncertainty to how many victims were killed by the same person. Eleven separate murders, stretching from 3 April 1888 to 13 February 1891, were included in a London Met Police investigation and were known collectively in the police docket as the “Whitchapel murders”. Opinions vary as to whether these murders should be linked to the same culprit, but five of the eleven Whitechapel murders, known as the “canonical five”, are widely believed to be the work of Jack the Ripper. Most experts point to deep throat slashes, abdominal and genital-area mutilation, removal of internal organs, and progressive facial mutilations as the distinctive features of the Ripper’s modus operandi. The first two cases in the Whitechapel murders file, those of Emma Elizabeth Smith and Martha Tabram, are not included in the canonical five.

Smith was robbed and sexually assaulted in Osborn Street, Whitechapel, on 3 April 1888. A blunt object was inserted into her vagina, rupturing her peritoneum. She developed peritonitis and died the following day at the London Hospital. She said that she had been attacked by two or three men, one of whom was a teenager. The attack was linked to the later murders by the press, but most authors attribute it to gang violence unrelated to the Ripper case.

Tabram was killed on 7 August 1888; she had suffered 39 stab wounds. The savagery of the murder, the lack of obvious motive, and the closeness of the location (George Yard, Whitechapel) and date to those of the later Ripper murders led police to link them. The attack differs from the canonical murders in that Tabram was stabbed rather than slashed at the throat and abdomen, and many experts do not connect it with the later murders because of the difference in the wound pattern.

Canonical five

The canonical five Ripper victims are Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary jane Kelly.

Nichols’ body was discovered at about 3:40 a.m. on Friday 31 August 1888 in Buck’s Row (now Durward Street), Whitechapel. The throat was severed by two cuts, and the lower part of the abdomen was partly ripped open by a deep, jagged wound. Several other incisions on the abdomen were caused by the same knife.

Chapman’s body was discovered at about 6 a.m. on Saturday 8 September 1888 near a doorway in the back yard of 29 Hanbury Street, Spitalfields. As in the case of Mary Ann Nichols, the throat was severed by two cuts. The abdomen was slashed entirely open, and it was later discovered that the uterus had been removed. At the inquest, one witness described seeing Chapman at about 5:30 a.m. with a dark-haired man of “shabby-genteel” appearance.

Stride and Eddowes were killed in the early morning of Sunday 30 September 1888. Stride’s body was discovered at about 1 a.m. in Dutfield’s Yard, off Berner Street (now Henriques Street) in Whitechapel. The cause of death was one clear-cut incision which severed the main artery on the left side of the neck. The absence of mutilations to the abdomen has led to uncertainty about whether Stride’s murder should be attributed to the Ripper or whether he was interrupted during the attack. Witnesses thought that they saw Stride with a man earlier that night but gave differing descriptions: some said that her companion was fair, others dark; some said that he was shabbily dressed, others well-dressed.

Eddowes’ body was found in Mitre Square in the City of London, three-quarters of an hour after Stride’s. The throat was severed and the abdomen was ripped open by a long, deep, jagged wound. The left kidney and the major part of the uterus had been removed. A local man named Joseph Lawende had passed through the square with two friends shortly before the murder, and he described seeing a fair-haired man of shabby appearance with a woman who may have been Eddowes. His companions were unable to confirm his description. Eddowes’ and Stride’s murders were later called the “double event”. Part of Eddowes’ bloodied apron was found at the entrance to a tenement in Goulston Street, Whitechapel. Some writing on the wall above the apron piece became known as the Goulston Street graffito and seemed to implicate a Jew or Jews, but it was unclear whether the graffito was written by the murderer as he dropped the apron piece, or was merely incidental. Such graffiti were commonplace in Whitechapel. Police Commissioner Charles Warren feared that the graffito might spark anti-semitic riots and ordered it washed away before dawn.

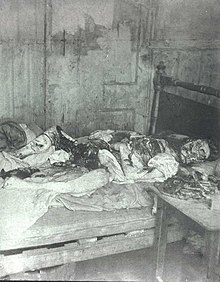

Kelly’s mutilated and disembowelled body was discovered lying on the bed in the single room where she lived at 13 Miller’s Court, off Dorset Street, Spitalfields, at 10:45 a.m. on Friday 9 November 1888. The throat had been severed down to the spine, and the abdomen almost emptied of its organs. The heart was missing.

The canonical five murders were perpetrated at night, on or close to a weekend, either at the end of a month or a week (or so) after. The mutilations became increasingly severe as the series of murders proceeded, except for that of Stride, whose attacker may have been interrupted. Nichols was not missing any organs; Chapman’s uterus was taken; Eddowes had her uterus and a kidney removed and her face mutilated; and Kelly’s body was eviscerated and her face hacked away, though only her heart was missing from the crime scene.

Historically, the belief that these five crimes were committed by the same man is derived from contemporary documents that link them together to the exclusion of others. In 1894, Sir Melville Macnaghten, Assistant Chief Constable of the Met Police and Head of the CID, wrote a report that stated: “the Whitechapel murderer had 5 victims—& 5 victims only”. Similarly, the canonical five victims were linked together in a letter written by police surgeon Thomas Bond to Robert Anderson, head of the London CID, on 10 November 1888. Some researchers have posited that some of the murders were undoubtedly the work of a single killer but an unknown larger number of killers acting independently were responsible for the others. Authors Stewart P. Evans and Donald Rumbelow argue that the canonical five is a “Ripper myth” and that three cases (Nichols, Chapman, and Eddowes) can be definitely linked but there is less certainty over Stride and Kelly. Conversely, others suppose that the six murders between Tabram and Kelly were the work of a single killer. Dr Percy Clark, assistant to the examining pathologist George Bagster Phillips, linked only three of the murders and thought that the others were perpetrated by “weak-minded individual[s] … induced to emulate the crime”. Macnaghten did not join the police force until the year after the murders, and his memorandum contains serious factual errors about possible suspects.

Later Whitechapel murders

Kelly is generally considered to be the Ripper’s final victim, and it is assumed that the crimes ended because of the culprit’s death, imprisonment, institutionalisation, or emigration. The Whitechapel murders file details another four murders that happened after the canonical five: those of Rose Mylett, Alice McKenzie, the Pinchin Street torso, and Frances Coles.

Mylett was found strangled in Clarke’s Yard, High Street, Poplar on 20 December 1888. There was no sign of a struggle, and the police believed that she had accidentally hanged herself on her collar while in a drunken stupor or committed suicide. Nevertheless, the inquest jury returned a verdict of murder.

McKenzie was killed on 17 July 1889 by severance of the left carotid artery. Several minor bruises and cuts were found on the body, discovered in Castle Alley, Whitechapel. One of the examining pathologists, Thomas Bond, believed this to be a Ripper murder, though his colleague George Bagster Phillips, who had examined the bodies of three previous victims, disagreed. Later writers are also divided between those who think that her murderer copied the Ripper’s modus operandi to deflect suspicion from himself, and those who ascribe it to the Ripper.

“The Pinchin Street torso” was a headless and legless torso of an unidentified woman found under a railway arch in Pinchin Street, Whitechapel, on 10 September1889. It seems probable that the murder was committed elsewhere and that parts of the dismembered body were dispersed for disposal.

Coles was killed on 13 February 1891 under a railway arch at Swallow Gardens, Whitechapel. Her throat was cut but the body was not mutilated. James Thomas Sadler was seen earlier with her and was arrested by the police, charged with her murder, and briefly thought to be the Ripper. He was discharged from court for lack of evidence on 3 March 1891.

Other alleged victims

In addition to the eleven Whitechapel murders, commentators have linked other attacks to the Ripper. In the case of “Fairy Fay”, it is unclear whether the attack was real or fabricated as a part of Ripper lore. “Fairy Fay” was a nickname given to a victim allegedly found on 26 December 1887 “after a stake had been thrust through her abdomen”, but there were no recorded murders in Whitechapel at or around Christmas 1887. “Fairy Fay” seems to have been created through a confused press report of the murder of Emma Elizabeth Smith, who had a stick or other blunt object shoved into her vagina. Most authors agree that the victim “Fairy Fay” never existed.

Annie Millwood was admitted to Whitechapel workhouse infirmary with stab wounds in the legs and lower torso on 25 February 1888. She was discharged but died from apparently natural causes aged 38 on 31 March 1888. She was later postulated as the Ripper’s first victim, but the attack cannot be linked definitely. Another supposed early victim was Ada Wilson, who reportedly survived being stabbed twice in the neck on 28 March 1888. Annie Farmer resided at the same lodging house as Martha Tabram and reported an attack on 21 November 1888. She had a superficial cut on her throat, but it was possibly self-inflicted.

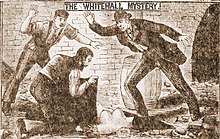

“The Whitechapel Mystery” was a term coined for the discovery of a headless torso of a woman on 2 October 1888 in the basement of the new Met Police HQ being built in Whitehall. An arm belonging to the body was previously discovered floating in the river Thames near Pimlico, and one of the legs was subsequently discovered buried near where the torso was found. The other limbs and head were never recovered and the body was never identified. The mutilations were similar to those in the Pinchin Street case, where the legs and head were severed but not the arms. The Whitehall Mystery and the Pinchin Street case may have been part of a series of murders called the “Thames Mysteries”, committed by a single serial killer dubbed the “Torso killer”. It is debatable whether Jack the Ripper and the “Torso killer” were the same person or separate serial killers active in the same area. The modus operandi of the Torso killer differed from that of the Ripper, and police at the time discounted any connection between the two. Elizabeth Jackson was a prostitute whose various body parts were collected from the river Thames over a three-week period in June 1889. She may have been another victim of the “Torso killer”.

John Gill, a seven-year-old boy, was found murdered in Manningham, Bradford, on 29 December 1888. His legs had been severed, his abdomen opened, his intestines drawn out, and his heart and one ear removed. The similarities with the murder of Mary Kelly led to press speculation that the Ripper had killed him.The boy’s employer, milkman William Barrett, was twice arrested for the murder but was released due to insufficient evidence. No one else was ever prosecuted.

Carrie Brown (nicknamed “Shakespeare”, reportedly for quoting Shakespeare’s sonnets) was strangled with clothing and then mutilated with a knife on 24 April 1891 in New York City. Her body was found with a large tear through her groin area and superficial cuts on her legs and back. No organs were removed from the scene, though an ovary was found upon the bed, either purposely removed or unintentionally dislodged. At the time, the murder was compared to those in Whitechapel, though the Metropolitan Police eventually ruled out any connection.

Investigation

The surviving police files on the Whitechapel murders allow a detailed view of investigative procedure in the Victorian era. A large team of policemen conducted house-to-house inquiries throughout Whitechapel. Forensic material was collected and examined. Suspects were identified, traced, and either examined more closely or eliminated from the inquiry. Modern police work follows the same pattern. More than 2,000 people were interviewed, “upwards of 300” people were investigated, and 80 people were detained.

The investigation was initially conducted by the Metropolitan Police Whitechapel (H) Division (CID) headed by Detective Inspector Edmund Reid. After the murder of Nichols, Detective Inspectors Frederick Abberline, Henry Moore, and Walter Andrews were sent from Central Office at Scotland Yard to assist. The City of London Police were involved under Detective Inspector James McWilliam after the Eddowes murder, which occurred within the City of London. The overall direction of the murder enquiries was hampered by the fact that the newly appointed head of the CID Robert Anderson was on leave in Switzerland between 7 September and 6 October, during the time when Chapman, Stride, and Eddowes were killed. This prompted Met Police Commissioner Sir Charles Warren to appoint Chief Inspector Donald Swanson to coordinate the enquiry from Scotland Yard.

A group of volunteer citizens in London’s East End called the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee patrolled the streets looking for suspicious characters, partly because of dissatisfaction with the police effort. They petitioned the government to raise a reward for information about the killer, and hired private detectives to question witnesses independently.

Butchers, slaughterers, surgeons, and physicians were suspected because of the manner of the mutilations. A surviving note from Major Henry Smith, Acting Commissioner of the City Police, indicates that the alibis were investigated of local butchers and slaughterers, with the result that they were eliminated from the inquiry. A report from Inspector Swanson to the Home Office confirms that 76 butchers and slaughterers were visited, and that the inquiry encompassed all their employees for the previous six months. Some contemporary figures, including Queen Victoria, thought the pattern of the murders indicated that the culprit was a butcher or cattle drover on one of the cattle boats that plied between London and mainland Europe. Whitechapel was close to the London Docks, and usually such boats docked on Thursday or Friday and departed on Saturday or Sunday. The cattle boats were examined but the dates of the murders did not coincide with a single boat’s movements and the transfer of a crewman between boats was also ruled out.

Criminal profiling

At the end of October, Robert Anderson asked police surgeon Thomas Bond to give his opinion on the extent of the murderer’s surgical skill and knowledge. The opinion offered by Bond on the character of the “Whitechapel murderer” is the earliest surviving offender profile. Bond’s assessment was based on his own examination of the most extensively mutilated victim and the post mortem notes from the four previous canonical murders. He wrote:

All five murders no doubt were committed by the same hand. In the first four the throats appear to have been cut from left to right, in the last case owing to the extensive mutilation it is impossible to say in what direction the fatal cut was made, but arterial blood was found on the wall in splashes close to where the woman’s head must have been lying.

All the circumstances surrounding the murders lead me to form the opinion that the women must have been lying down when murdered and in every case the throat was first cut.

Bond was strongly opposed to the idea that the murderer possessed any kind of scientific or anatomical knowledge, or even “the technical knowledge of a butcher or horse slaughterer”. In his opinion, the killer must have been a man of solitary habits, subject to “periodical attacks of homicidal and erotic mania”, with the character of the mutilations possibly indicating “satyriasis”. Bond also stated that “the homicidal impulse may have developed from a revengeful or brooding condition of the mind, or that religious mania may have been the original disease but I do not think either hypothesis is likely”.

There is no evidence of any sexual activity with any of the victims, yet psychologists suppose that the penetration of the victims with a knife and “leaving them on display in sexually degrading positions with the wounds exposed” indicates that the perpetrator derived sexual pleasure from the attacks. This view is challenged by others who dismiss such hypotheses as insupportable supposition.

Suspects

The concentration of the killings around weekends and public holidays and within a few streets of each other has indicated to many that the Ripper was in regular employment and lived locally.Others have thought that the killer was an educated upper-class man, possibly a doctor or an aristocrat who ventured into Whitechapel from a more well-to-do area. Such theories draw on cultural perceptions such as fear of the medical profession, mistrust of modern science, or the exploitation of the poor by the rich. Suspects proposed years after the murders include virtually anyone remotely connected to the case by contemporary documents, as well as many famous names who were never considered in the police investigation. Everyone alive at the time is now dead, and modern authors are free to accuse anyone “without any need for any supporting historical evidence”. Suspects named in contemporary police documents include three in Sir Melville Macnaghten’s 1894 memorandum, but the evidence against them is circumstantial at best.

There are many and varied theories about the identity and profession of Jack the Ripper, but authorities are not agreed upon any of them, and the number of named suspects reaches over one hundred. Despite continued interest in the case, the Ripper’s true identity remains unknown to this day, and will likely remain so.

Letters

Over the course of the Ripper murders, the police, newspapers, and others received hundreds of letters regarding the case. Some were well-intentioned offers of advice for catching the killer, but the vast majority were useless.

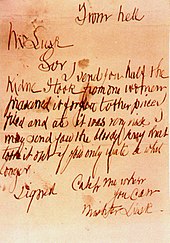

Hundreds of letters claimed to have been written by the killer himself, and three of these in particular are prominent: the “Dear Boss” letter, the “Saucy Jacky” postcard and the “From Hell” letter.

The “Dear Boss” letter, dated 25 September, was postmarked 27 September 1888. It was received that day by the Central News Agency, and was forwarded to Scotland Yard on 29 September.Initially it was considered a hoax, but when Eddowes was found three days after the letter’s postmark with one ear partially cut off, the letter’s promise to “clip the ladys (sic) ears off” gained attention. Eddowes’ ear appears to have been nicked by the killer incidentally during his attack, and the letter writer’s threat to send the ears to the police was never carried out. The name “Jack the Ripper” was first used in this letter by the signatory and gained worldwide notoriety after its publication. Most of the letters that followed copied this letter’s tone. Some sources claim that another letter dated 17 September 1888 was the first to use the name “Jack the Ripper”, but most experts believe that this was a fake inserted into police records in the 20th century.

The “Saucy Jacky” postcard was postmarked 1 October 1888 and was received the same day by the Central News Agency. The handwriting was similar to the “Dear Boss” letter. It mentions that two victims were killed very close to one another: “double event this time”, which was thought to refer to the murders of Stride and Eddowes. It has been argued that the letter was posted before the murders were publicised, making it unlikely that a crank would have such knowledge of the crime, but it was postmarked more than 24 hours after the killings took place, long after details were known and being published by journalists and talked about by residents of the area.

The “From Hell” letter was received by George Lusk, leader of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, on 16 October 1888. The handwriting and style is unlike that of the “Dear Boss” letter and “Saucy Jacky” postcard. The letter came with a small box in which Lusk discovered half of a kidney, preserved in “spirits of wine” (ethanol). Eddowes’ left kidney had been removed by the killer. The writer claimed that he “fried and ate” the missing kidney half. There is disagreement over the kidney; some contend that it belonged to Eddowes, while others argue that it was a macabre practical joke. The kidney was examined by Dr Thomas Openshaw of the London Hospital, who determined that it was human and from the left side, but (contrary to false newspaper reports) he could not determine any other biological characteristics. Openshaw subsequently also received a letter signed “Jack the Ripper”.

Scotland Yard published facsimiles of the “Dear Boss” letter and the postcard on 3 October, in the ultimately vain hope that someone would recognise the handwriting. Charles Warren explained in a letter to Godfrey Lushington, Permanent Under-Secretary of State for the Home Department: “I think the whole thing a hoax but of course we are bound to try & ascertain the writer in any case.” On 7 October 1888, George R. Sims in the Sunday newspaper Referee implied scathingly that the letter was written by a journalist “to hurl the circulation of a newspaper sky high”. Police officials later claimed to have identified a specific journalist as the author of both the “Dear Boss” letter and the postcard. The journalist was identified as Tom Bullen in a letter from Chief Inspector John Littlechild to George R. Sims dated 23 September 1913. A journalist called Fred Best reportedly confessed in 1931 that he and a colleague at The Star had written the letters signed “Jack the Ripper” to heighten interest in the murders and “keep the business alive”.

Media

The Ripper murders mark an important watershed in the treatment of crime by journalists. Jack the Ripper was not the first serial killer, but his case was the first to create a worldwide media frenzy. Tax reforms in the 1850s had enabled the publication of inexpensive newspapers with wider circulation. These mushroomed in the later Victorian era to include mass-circulation newspapers as cheap as a halfpenny, along with popular magazines such as The Illustrated Police News which made the Ripper the beneficiary of previously unparalleled publicity.

After the murder of Nichols in early September, the Manchester Guardian reported that: “Whatever information may be in the possession of the police they deem it necessary to keep secret … It is believed their attention is particularly directed to … a notorious character known as ‘Leather Apron’.” Journalists were frustrated by the unwillingness of the CID to reveal details of their investigation to the public, and so resorted to writing reports of questionable veracity. Imaginative descriptions of “Leather Apron” appeared in the press, but rival journalists dismissed these as “a mythical outgrowth of the reporter’s fancy”. John Pizer, a local Jew who made footwear from leather, was known by the name “Leather Apron” and was arrested, even though the investigating inspector reported that “at present there is no evidence whatsoever against him”. He was soon released after the confirmation of his alibis.

After the publication of the “Dear Boss” letter, “Jack the Ripper” supplanted “Leather Apron” as the name adopted by the press and public to describe the killer. The name “Jack” was already used to describe another fabled London attacker: “Spring-heeled Jack”, who supposedly leapt over walls to strike at his victims and escape as quickly as he came. The invention and adoption of a nickname for a particular killer became standard media practice with examples such as the Axeman of New Orleans, the Boston Strangler, and the Beltway Sniper. Examples derived from Jack the Ripper include the French Ripper, the Dusseldorf Ripper, the Camden Ripper, the Blackout Ripper, the Yorkshire Ripper and the Rostov Ripper.

Legacy

The nature of the murders and of the victims drew attention to the poor living conditions in the East End and galvanised public opinion against the overcrowded, unsanitary slums. In the two decades after the murders, the worst of the slums were cleared and demolished, but the streets and some buildings survive and the legend of the Ripper is still promoted by guided tours of the murder sites. The ten Bells public house in Commercial Street was frequented by at least one of the victims and was the focus of such tours for many years. In 2015, the Jack the Ripper Museum opened in east London.

In the immediate aftermath of the murders and later, “Jack the Ripper became the children’s bogey man.” Depictions were often phantasmic or monstrous. In the 1920s and 1930s, he was depicted in film dressed in everyday clothes as a man with a hidden secret, preying on his unsuspecting victims; atmosphere and evil were suggested through lighting effects and shadowplay. By the 1960s, the Ripper had become “the symbol of a predatory aristocracy”, and was more often portrayed in a top hat dressed as a gentleman. The Establishment as a whole became the villain, with the Ripper acting as a manifestation of upper-class exploitation. The image of the Ripper merged with or borrowed symbols from horror stories, such as Dracula’s cloak or Victor Frankenstein’s organ harvest.

In addition to the contradictions and unreliability of contemporary accounts, attempts to identify the real killer are hampered by the lack of surviving forensic evidence. DNA analysis on extant letters is inconclusive; the available material has been handled many times and is too contaminated to provide meaningful results.There have been mutually incompatible claims that DNA evidence points conclusively to two different suspects, and the methodology of both has also been criticised.

Jack the Ripper features in hundreds of works of fiction and works which straddle the boundaries between fact and fiction, including the Ripper letters and a hoax Diary of Jack the Ripper. The Ripper appears in novels, short stories, poems, comic books, games, songs, plays, operas, television programmes, and films. More than 100 non-fiction works deal exclusively with the Jack the Ripper murders, making it one of the most written-about true-crime subjects. The term “ripperology” was coined by Colin Wilson in the 1970s to describe the study of the case by professionals and amateurs. The periodicals Ripperana, Ripperologist, and Ripper Notes publish their research.

There is no waxwork figure of Jack the Ripper at Madame Tussauds’ Chamber of Horrors, unlike murderers of lesser fame, in accordance with their policy of not modelling persons whose likeness is unknown. He is instead depicted as a shadow. In 2006, BBC History magazine and its readers selected Jack the Ripper as the worst Briton in history.