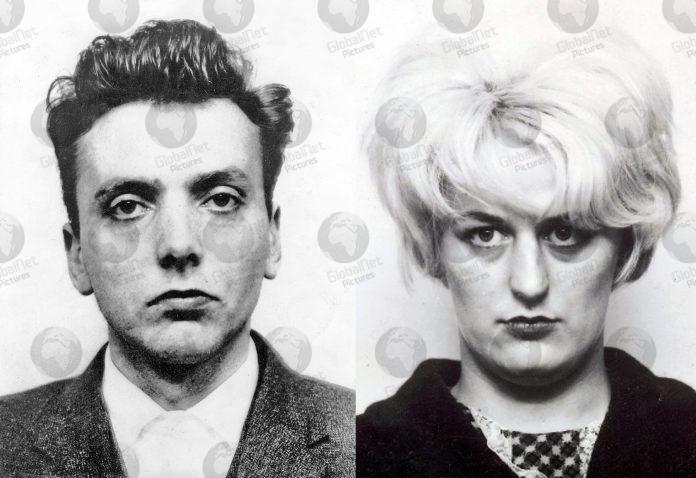

Ian Brady & Myra Hindley

The Moors murders were carried out by Ian Brady and Myra Hindley between July 1963 and October 1965, in and around Manchester in England. The victims were five children aged between 10 and 17—Pauline Reade, John Kilbride, Keith Bennett, Lesley Ann Downey and Edward Evans—at least four of whom were sexually assaulted. Two of the victims were discovered in graves dug on Saddleworth Moor; a third grave was discovered there in 1987, more than twenty years after Brady and Hindley’s trial. The body of a fourth victim, Keith Bennett, is also suspected to be buried there, but despite repeated searches it remains undiscovered.

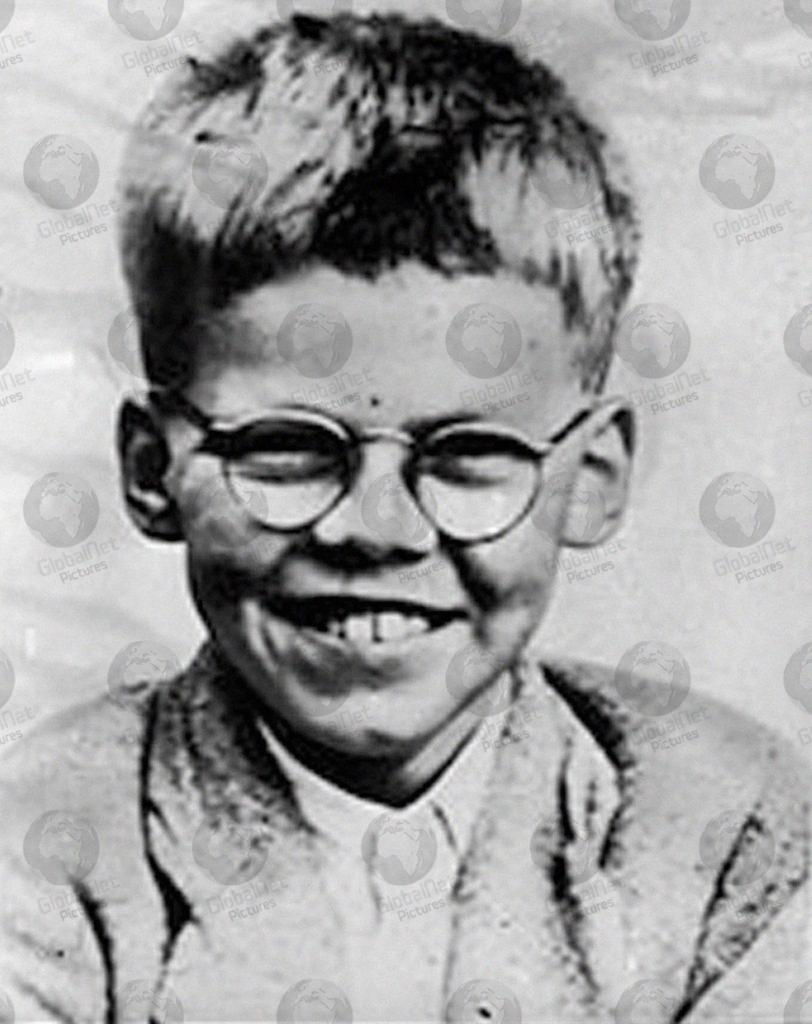

Keith Bennett

The police were initially aware of only three killings, those of Edward Evans, Lesley Ann Downey and John Kilbride. The investigation was reopened in 1985, after Brady was reported in the press as having confessed to the murders of Pauline Reade and Keith Bennett. Brady and Hindley were taken separately to Saddleworth Moor to assist the police in their search for the graves, both by then having confessed to the additional murders.

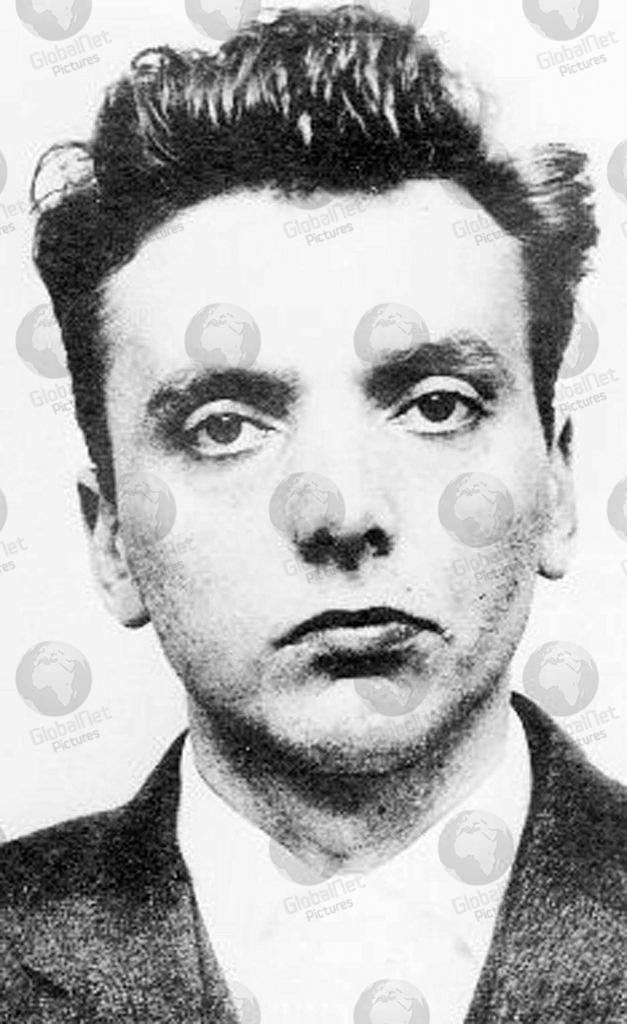

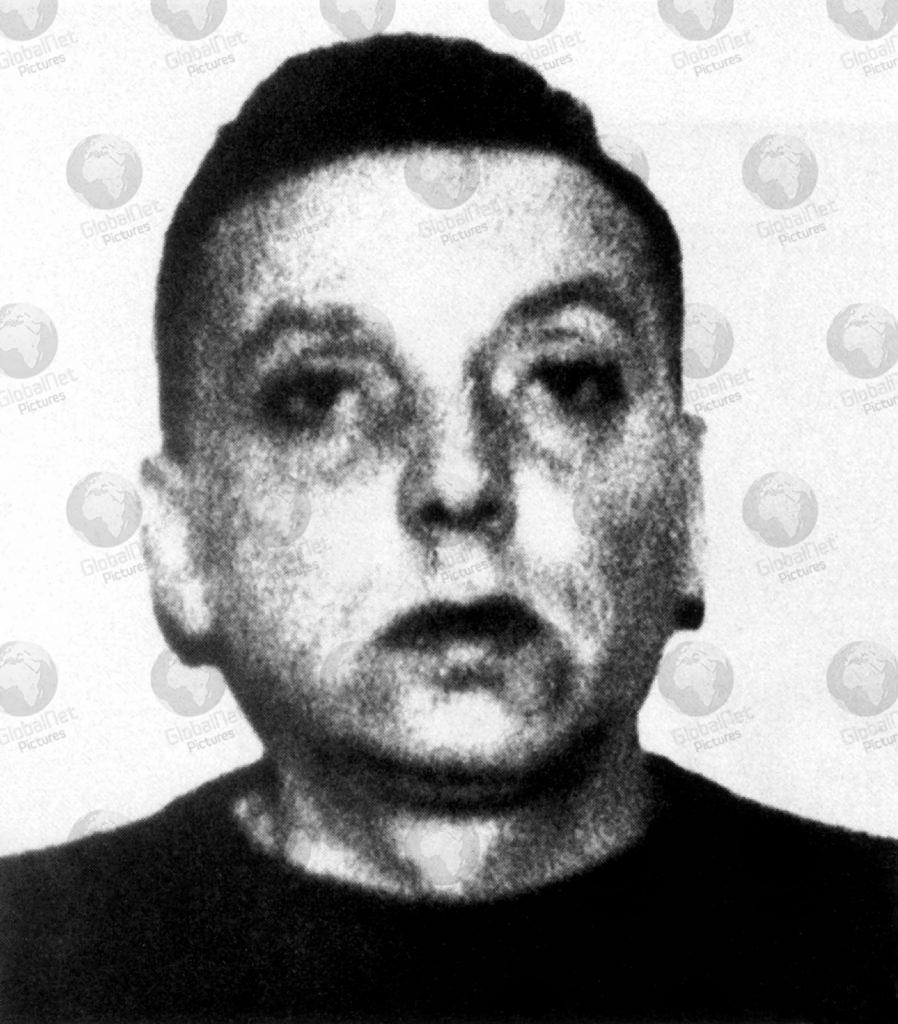

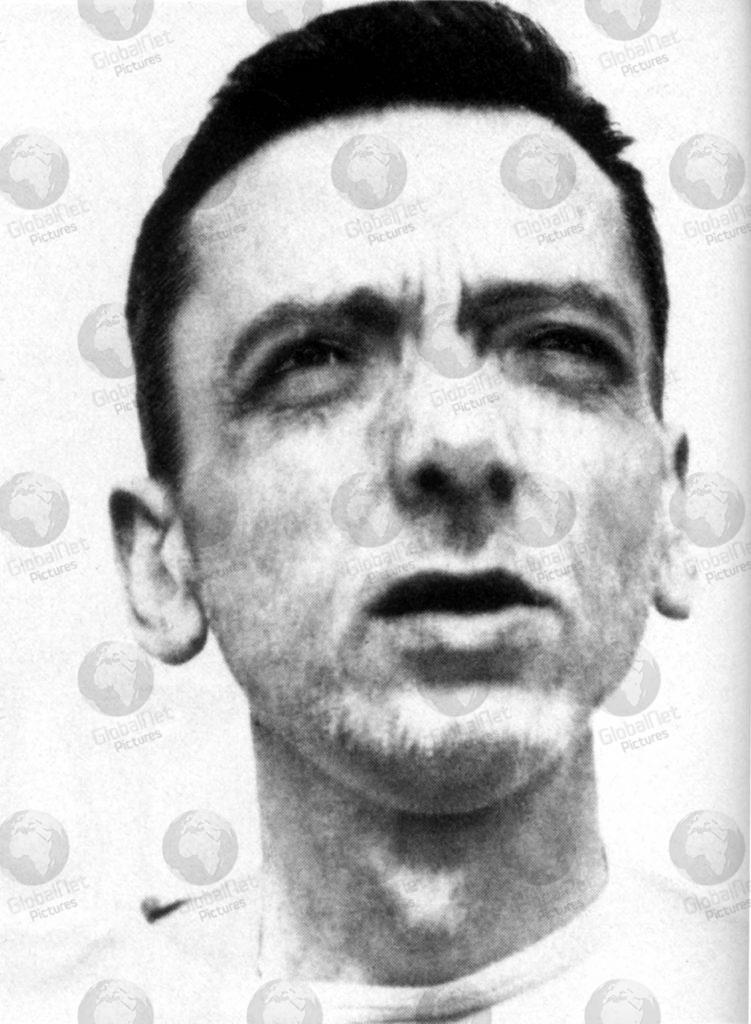

Mugshots of moors murders child killers Ian brady and Myra Hindley

Characterised by the press as “the most evil woman in Britain”, Hindley made several appeals against her life sentence, claiming she was a reformed woman and no longer a danger to society, but was never released. She died in 2002, aged 60. Brady was declared criminally insane in 1985 and confined in the high-security Ashworth Hospital. He made it clear that he never wished to be released, and repeatedly asked to be allowed to die. He died in 2017, in Ashworth, aged 79.

The murders were the result of what Malcolm MacCulloch, professor of forensic psychiatry at Cardiff University, called a “concertenation of circumstances”. The trial judge, Mr Justice Fenton Atkinson, described Brady and Hindley in his closing remarks as “two sadistic killers of the utmost depravity”.

Ian Brady

Ian Brady was born in Glasgow as Ian Duncan Stewart on 2 January 1938 to Margaret “Peggy” Stewart, an unmarried tea room waitress. The identity of Brady’s father has never been reliably ascertained, although his mother said he was a reporter working for a Glasgow newspaper, who died three months before Brady was born. Stewart had little support, and after a few months was forced to give her son into the care of Mary and John Sloan, a local couple with four children of their own. Brady took their name, and became known as Ian Sloan. His mother continued to visit him throughout his childhood. Various authors have stated that he tortured animals, although Brady objected to such accusations. Aged nine, he visited Loch Lomond with his family, where he reportedly discovered an affinity for the outdoors, and a few months later the family moved to a new council house on an overspill estate at Pollok. He was accepted for Shawlands Academy, a school for above-average pupils.

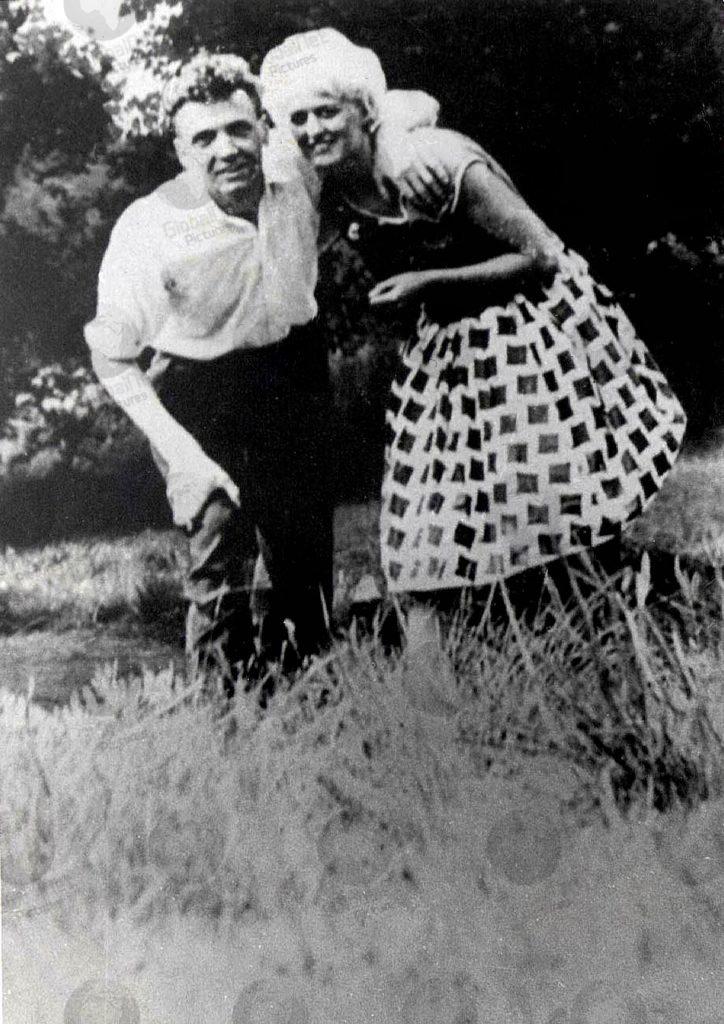

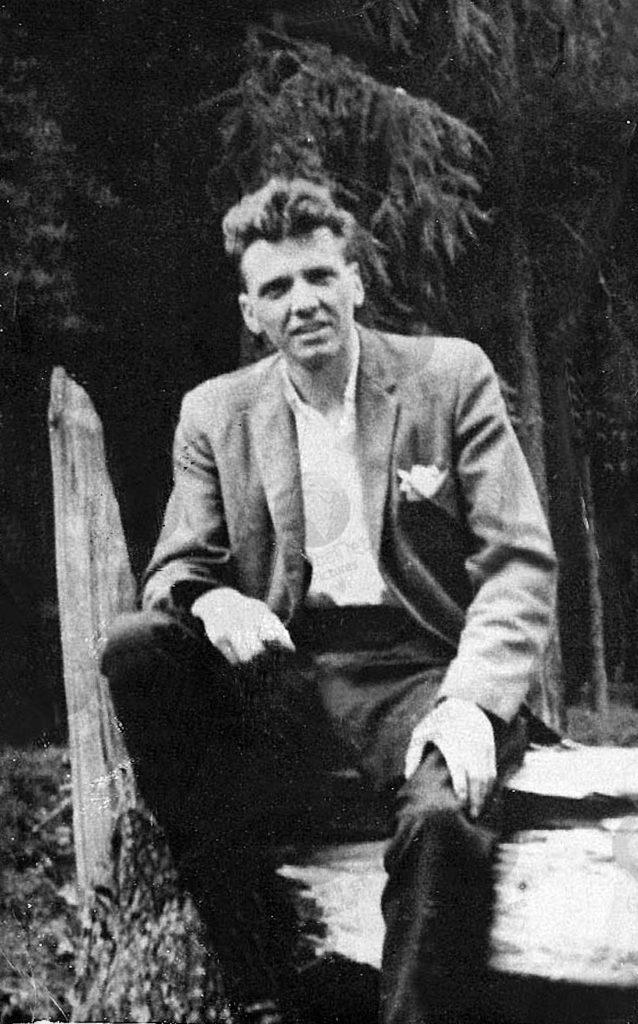

Exclusive picture of Moors murderer Ian Brady sitting on Saddleworth Moor where he buried his victims

At Shawlands his behaviour worsened; as a teenager he twice appeared before a juvenile court for housebreaking. He left the academy aged 15, and took a job as a tea boy at a Harland and Wolff shipyard in Govan. Nine months later, he began working as a butcher’s messenger boy. He had a girlfriend, Evelyn Grant, but their relationship ended when he threatened her with a flick knife after she visited a dance with another boy. He again appeared before the court, this time with nine charges against him, and shortly before his 17th birthday he was placed on probation, on condition that he live with his mother. By then she had moved to Manchester and married an Irish fruit merchant named Patrick Brady, and it was the latter who got Brady a job as a fruit porter at Smithfield Market. Ian took his new stepfather’s surname.

Within a year of moving to Manchester, Ian Brady was caught with a sack full of lead seals he had stolen and was trying to smuggle out of the market. He was sent to Strangeways for three months. As he was still under 18, he was sentenced to two years in borstal for “training”. He was sent to Latchmere House in London, and then Hatfield borstal in the West Riding of Yorkshire. After being discovered drunk on alcohol he had brewed he was moved to the much tougher unit at Hull. Released on 14 November 1957, Brady returned to Manchester, where he took a labouring job, which he hated, and was dismissed from another job in a brewery. Deciding to “better himself”, he obtained a set of instruction manuals on book-keeping from a local public library, with which he “astonished” his parents by studying alone in his room for hours.

In January 1959, Brady applied for and was offered a clerical job at Millwards, a wholesale chemical distribution company based in Gorton. He was regarded by his colleagues as a quiet, punctual, but short-tempered young man. He read books including Teach Yourself German and Mein Kampf, as well as works on Naziatrocities. He rode a Tiger Cub motorcycle, which he used to visit the Pennines.

Myra Hindley

Myra Hindley was born in Crumpsall on 23 July 1942 and raised in Gorton, then a working-class area of Manchester. Her parents, Nellie and Bob Hindley (the latter an alcoholic), beat her regularly when she was a young child. The small house the family lived in was in such poor condition that Hindley and her parents had to sleep in the only available bedroom, she in a single bed next to her parents’ double. The family’s living conditions deteriorated further when Hindley’s sister, Maureen, was born in August 1946. About a year after the birth, Hindley, then 5, was sent by her parents to live with her grandmother, whose home was nearby.

Hindley’s father had served with the Parachute Regiment and had been stationed in North Africa, Cyprus and Italy during the Second World War. He had been known in the army as a “hard man” and he expected his daughter to be equally tough; he taught her how to fight, and insisted that she “stick up for herself”. When Hindley was 8, a local boy approached her in the street and scratched both of her cheeks with his fingernails, drawing blood. She burst into tears and ran into her parents’ house, to be met by her father, who demanded that she “Go and punch him [the boy], because if you don’t I’ll leather you!” Hindley found the boy and succeeded in knocking him down with a sequence of punches, as her father had taught her. As she wrote later, “at eight years old I’d scored my first victory”.

Malcolm MacCulloch, professor of forensic psychiatry at Cardiff University, has suggested that the fight, and the part that Hindley’s father played in it, may be “key pieces of evidence” in trying to understand Hindley’s role in the Moors murders:

The relationship with her father brutalised her … She was not only used to violence in the home but rewarded for it outside. When this happens at a young age it can distort a person’s reaction to such situations for life.

One of her closest friends was 13-year-old Michael Higgins, who lived on a nearby street. In June 1957, he invited her to go swimming with friends at a local disused reservoir. Although she was a good swimmer, Hindley chose not to go and instead went out with a friend, Pat Jepson. Higgins drowned in the reservoir, and upon learning of his fate, Hindley was deeply upset and blamed herself for his death. She collected for a funeral wreath, and his funeral at St Francis’s Monastery in Gorton Lane—the church where Hindley had been baptised a Catholic on 16 August 1942—had a lasting effect on her. Hindley’s mother had agreed to her father’s insistence that she be baptised a Catholic only on the condition that she was not sent to a Catholic school, as her mother believed that “all the monks taught was the catechism. Hindley was increasingly drawn to the Catholic Church after she started at Ryder Brow Secondary Modern, and began taking instruction for formal reception into the Church soon after Higgins’s funeral. She took the confirmation name of Veronica, and received her first communion in November 1958.

Hindley’s first job was as a junior clerk at a local electrical engineering firm. She ran errands, made tea, and typed. She was well liked at the firm, enough so that when she lost her first week’s wage packet, the other girls had a collection to replace it. Beginning at Christmas 1958, Hindley began a short relationship with Ronnie Sinclair, and became engaged at 17. The engagement was called off several months later; Hindley apparently thought Sinclair immature, and unable to provide her with the life she envisaged for herself. Shortly after her 17th birthday, she changed her hair colour with a pink rinse. She took judo lessons once a week at a local school, but found partners reluctant to train with her, as she was often slow to release her grip. She took a job at Bratby and Hinchliffe, an engineering company in Gorton, but was dismissed for absenteeism after six months.

As murderers

Chris Cowley

Hindley claimed that Brady began to talk about “committing the perfect murder” in July 1963, and often spoke to her about Meyer Levin’s Compulsion, published as a novel in 1956 and adapted for the cinema in 1959. The story tells a fictionalised account of the Loepold and Loeb case, two young men from well-to-do families who attempt to commit the perfect murder of a 12-year-old boy, and escape the death penalty because of their age.

By June 1963, Brady had moved in with Hindley at her grandmother’s house in Bannock Street, and on 12 July 1963, the two murdered their first victim, 16-year-old Pauline Reade. Reade had attended school with Hindley’s younger sister, Maureen, and had also been in a short relationship with David Smith, a local boy with three criminal convictions for minor crimes. Police could find nobody who had seen Reade before her disappearance, and although the 15-year-old Smith was questioned by police, he was cleared of any involvement in her death. Their next victim, John Kilbride, was killed on 23 November 1963. A huge search was undertaken, with over 700 statements taken, and 500 “missing” posters printed. Eight days after he failed to return home, 2,000 volunteers scoured waste ground and derelict buildings.

Hindley hired a vehicle a week after Kilbride went missing, and again on 21 December 1963, apparently to make sure the burial sites had not been disturbed. In February 1964, she bought a second-hand Austin Traveller, but soon after traded it for a Mini van. Twelve-year-old Keith Bennett disappeared on 16 June 1964. His stepfather, Jimmy Johnson, became a suspect; in the two years following Bennett’s disappearance, Johnson was taken for questioning on four occasions. Detectives searched under the floorboards of the Johnsons’ house, and on discovering that the houses in the row were connected, extended the search to the entire street.

Maureen Hindley married David Smith on 15 August 1964. The marriage was hastily arranged and performed at a register office. None of Hindley’s relatives attended; Myra did not approve of the marriage, and her mother was too embarrassed—Maureen was seven months pregnant. The newlyweds moved into Smith’s father’s house. The next day, Brady suggested that the four take a day-trip to Windermere. This was the first time Brady and Smith had met properly, and Brady was apparently impressed by Smith’s demeanour. The two talked about society, the distribution of wealth, and the possibility of robbing a bank. The young Smith was similarly impressed by Brady, who throughout the day had paid for his food and wine. The trip to the Lake District was the first of many outings. Hindley was apparently jealous of their relationship, but became closer to her sister.

In 1964, Hindley, her grandmother, and Brady were rehoused as part of the post-war slum clearances in Manchester, to 16 Wardle Brook Avenue in the new overspill estate of Hattersley. Brady and Hindley became friendly with Patricia Hodges, an 11-year-old girl who lived at 12 Wardle Brook Avenue. Hodges accompanied the two on their trips to Saddleworth Moor to collect peat, something that many householders on the new estate did to improve the soil in their gardens, which were full of clay and builder’s rubble. She remained unharmed; living only a few doors away, her disappearance would have been easily solved.

Early on Boxing Day 1964, Hindley left her grandmother at a relative’s house and refused to allow her back to Wardle Brook Avenue that night. On the same day, 10-year-old Lesley Ann Downey disappeared from a funfair in Ancoats. Despite a huge search, she was not found. The following day, Hindley brought her grandmother back home. By February 1965, Patricia Hodges had stopped visiting 16 Wardle Brook Avenue, but David Smith was still a regular visitor. Brady gave Smith books to read, and the two discussed robbery and murder. On Hindley’s 23rd birthday, her sister and brother-in-law, who had until then been living with relatives, were rehoused in Underwood Court, a block of flats not far from Wardle Brook Avenue. The two couples began to see each other more regularly, but usually only on Brady’s terms.

During the 1990s, Hindley claimed that she took part in the killings only because Brady had drugged her, was blackmailing her with pornographic pictures he had taken of her, and had threatened to kill her younger sister, Maureen. In a 2008 television documentary series on female serial killers broadcast on ITV3, Hindley’s solicitor, Andrew McCooey, reported that she had said to him:

I ought to have been hanged. I deserved it. My crime was worse than Brady’s because I enticed the children and they would never have entered the car without my role … I have always regarded myself as worse than Brady.

Arrest

Early on the morning of 7 October 1965, shortly after Smith’s call, Superintendent Bob Talbot of the Cheshire Police arrived at the back door of 16 Wardle Brook Avenue, wearing a borrowed baker’s overall to cover his uniform. Talbot identified himself to Hindley as a police officer when she opened the door, and told her that he wanted to speak to her boyfriend. Hindley led him into the living room, where Brady was sitting up in a divan writing a note to his employer explaining that he would not be able to get into work because of his ankle injury. Talbot explained that he was investigating “an act of violence involving guns” that was reported to have taken place the previous evening.

Hindley denied there had been any violence, and allowed police to look around the house. When they came to the upstairs room in which Evans’s body was stored the police found the door locked, and asked Brady for the key. Hindley claimed that the key was at work, but after the police offered to drive her to her employer’s premises to retrieve it, Brady told her to hand the key over. When they returned to the living room, the police told Brady that they had discovered a trussed up body, and that he was being arrested on suspicion of murder. As Brady was getting dressed, he said “Eddie and I had a row and the situation got out of hand.”

Hindley was not arrested with Brady, but she demanded to go with him to the police station, accompanied by her dog, Puppet, to which the police agreed. Hindley was questioned about the events surrounding Evans’s death, but she refused to make any statement beyond claiming that it had been an accident. As the police had no evidence that Hindley was involved in Evans’s murder, she was allowed to go home, on the condition that she return the next day for further questioning. Hindley was at liberty for four days following Brady’s arrest, during which time she went to her employer’s premises and asked to be dismissed, so that she would be eligible for unemployment benefits. While in the office where Brady worked, she found some papers belonging to him in an envelope that she claimed she did not open, which she burned in an ashtray. She believed that they were plans for bank robberies, nothing to do with the murders. On 11 October, Hindley was charged as an accessory to the murder of Edward Evans and was remanded at Riseley.

Investigation

Brady admitted under police questioning that he and Evans had fought, but insisted that he and Smith had murdered Evans between them; Hindley, he said, had “only done what she had been told”. Smith told police that Brady had asked him to return anything incriminating, such as “dodgy books”, which Brady then packed into suitcases. Smith had no idea what else the suitcases contained or where they might be, but he mentioned in passing that Brady “had a thing about railway stations”. The police consequently requested a search of all Manchester’s left-luggage offices for any suitcases belonging to Brady, and on 15 October British Transport Police found what they were looking for at Manchester Central Railway station—the left-luggage ticket was found several days later in the back of Hindley’s prayer book.

Inside one of the suitcases were nine pornographic photographs taken of a young girl, naked and with a scarf tied across her mouth, and a 16-minute tape recording of her screaming and pleading for help. Ann Downey, Lesley Ann Downey’s mother, later listened to the tape after police had discovered the body of her missing 10-year-old daughter, and confirmed that it was a recording of her daughter’s voice.

Hindley, meanwhile, had been arrested on 11 October after new evidence had emerged during the continuing investigation to convince police that she had also been actively involved in the murder of Edward Evans. She and Brady were both charged with the murder of Edward Evans, while police searched the moors for further victims.

Police searching the house at Wardle Brook Avenue found an old exercise book in which the name “John Kilbride” had been scribbled, which made them suspicious that Brady and Hindley might have been involved in the unsolved disappearances of other youngsters. A large collection of photographs was discovered in the house, many of which seemed to have been taken on Saddleworth Moor. One hundred and fifty officers were drafted to search the moor, looking for locations that matched the photographs. Initially the search was concentrated along the A628 road near Woodhead, but a close neighbour, 11-year-old Pat Hodges, had on several occasions been taken to the moor by Brady and Hindley and she was able to point out their favourite sites along the A635 road. On 16 October, police found an arm bone sticking out of the peat; officers presumed that they had found the body of John Kilbride, but soon discovered that it was that of Lesley Ann Downey. Her mother Ann West had been on the moor watching as the police conducted their search, but was not present when the body was found. The body of Lesley Ann Downey was still visually identifiable when recovered. She was shown clothing recovered from the grave, and identified it as belonging to her missing daughter.

The investigating officers suspected Brady and Hindley of murdering other missing children and teenagers who had disappeared from areas in and around Manchester over the previous few years, and the search for bodies continued after the discovery of John Kilbride’s body, but with winter setting in it was called off in November. Presented with the evidence of the tape recording, Brady admitted to taking the photographs of Lesley Ann Downey, but insisted that she had been brought to Wardle Brook Avenue by two men who had subsequently taken her away again, alive. By 2 December 1965, Brady had been charged with the murders of John Kilbride, Lesley Ann Downey and Edward Evans. Hindley had been charged with the murders of Lesley Ann Downey and Edward Evans, and being an accessory to the murder of John Kilbride. At the committal hearing on 6 December, Brady was charged with the murders of Edward Evans, John Kilbride, and Lesley Ann Downey, and Hindley with the murders of Edward Evans and Lesley Ann Downey, as well as with harbouring Brady in the knowledge that he had killed John Kilbride. The prosecution’s opening statement was held in camera rather than in open court, and the defence asked for a similar stipulation but was refused.The proceedings continued in front of three magistrates in Hyde over an 11-day period during December, at the end of which the pair were committed for trial at Chester Assizes.

Many of the photographs taken by Brady and Hindley on the moor featured Hindley’s dog Puppet, sometimes as a puppy. Detectives arranged for the animal to be examined by a veterinary surgeon to determine its age, from which they could date when the pictures were taken. The examination involved an analysis of the dog’s teeth, which required a general anaesthetic from which Puppet did not recover, as he suffered from an undiagnosed kidney complaint. On hearing the news of her dog’s death, Hindley became furious, and accused the police of murdering Puppet, one of the few occasions detectives witnessed any emotional response from her.

In a letter to her mother shortly afterwards, Hindley wrote:

‘I feel as though my heart’s been torn to pieces. I don’t think anything could hurt me more than this has. The only consolation is that some moron might have got hold of Puppet and hurt him.’

Trial

The trial was held over 14 days beginning on 19 April 1966, in front of Mr Justice Fenton Atkinson. Such was the public interest that the courtroom was fitted with security screens to protect Brady and Hindley. The pair were each charged with three murders, those of Evans, Downey and Kilbride, as it was considered that there was by then sufficient evidence to implicate Hindley in Kilbride’s death. The attorney general, Sir Frederick Elwyn Jones, led the prosecution, assisted by William Mars-Jones. Brady was defended by the Liberal Member of Parliament Emlyn Hooson and Hindley was defended by Godfrey Heilpern, recorder of Salford from 1964—both experienced Queen’s Counsels (QCs) David Smith was the chief prosecution witness, but during the trial it was revealed that he had entered into an agreement with a newspaper that he initially refused to name—even under intense questioning—guaranteeing him £1,000 (equivalent to about £20,000 in 2019) for the syndication rights to his story if Brady and Hindley were convicted, something the trial judge described as a “gross interference with the course of justice”. Smith finally admitted in court that the newspaper was the News of the World which had already paid for a holiday in France for him and his wife and was paying him a regular income of £20 per week, as well as accommodating him in a five-star hotel for the duration of the trial.

Brady and Hindley pleaded not guilty to the charges against them; both were called to give evidence, Brady for over eight hours and Hindley for six. Although Brady admitted to hitting Evans with an axe, he did not admit to killing him, arguing that the pathologist in his report had stated that Evans’s death was “accelerated by strangulation”. Under cross-examination by the prosecuting counsel, all Brady would admit was that “I hit Evans with the axe. If he died from axe blows, I killed him.” Hindley denied any knowledge that the photographs of Saddleworth Moor found by police had been taken near the graves of their victims.

A 16-minute tape recording of Lesley Anne Downey, on which the voices of Brady and Hindley were audible, was played in open court. Hindley admitted that her attitude towards Downey was “brusque and cruel”, but claimed that was only because she was afraid that someone might hear Downey screaming. Hindley claimed that when Downey was being undressed she herself was “downstairs”; when the pornographic photographs were taken she was “looking out the window”; and that when Downey was being strangled she “was running a bath”.

On 6 May, after having deliberated for a little over two hours, the jury found Brady guilty of all three murders and Hindley guilty of the murders of Downey and Evans. As the death penalty for murder had been abolished while Brady and Hindley were held on remand, the judge passed the only sentence that the law allowed: life imprisonment. Brady was sentenced to three concurrent life sentences and Hindley was given two, plus a concurrent seven-year term for harbouring Brady in the knowledge that he had murdered John Kilbride. Brady was taken to Durham Prison and Hindley was sent to Holloway Prison.

In his closing remarks Atkinson described the murders as a “truly horrible case” and condemned the accused as “two sadistic killers of the utmost depravity”. He recommended that both Brady and Hindley spend “a very long time” in prison before being considered for parole but did not stipulate a tariff. He stated that Brady was “wicked beyond belief” and that he saw no reasonable possibility of reform. He did not consider that the same was necessarily true of Hindley, “once she is removed from [Brady’s] influence”. Throughout the trial Brady and Hindley “stuck rigidly to their strategy of lying”, and Hindley was later described as “a quiet, controlled, impassive witness who lied remorselessly”.

Later investigation

In 1985, Brady allegedly confessed to Fred Harrison, a journalist working for The Sunday People, that he had also been responsible for the murders of Pauline Reade and Keith Bennett, something that the police already suspected, as both children lived in the same area as Brady and Hindley and had disappeared at about the same time as their other victims. The subsequent newspaper reports prompted Greater Manchester Police (GMP) to reopen the case, in an investigation headed by Detective Chief Superintendent Peter Topping, who had been appointed head of GMP’s(CID) the previous year.

Since the Moors Murders came to light in 1965, regional and national newspapers had been keen to name other missing children and teenagers from in and near the Manchester area as possible victims of Brady and Hindley. One victim was Stephen Jennings, a three-year-old West Yorkshire boy who was last seen alive in December 1962. His body was finally found buried in a field in 1988, but the following year his father William Jennings was found guilty of his murder. Jennifer Tighe, a 14-year-old girl who disappeared from an Oldham children’s home in December 1964, was mentioned in the press as a possible Moors Murders victim some 40 years later, but after a few more years Greater Manchester Police confirmed that she was indeed still alive. This followed claims in February 2004 that Hindley had confessed to another inmate that she and Brady had murdered a sixth victim, a teenage girl.

On 3 July 1985, DCS Topping visited Brady, then being held at Gartree Prison, Leics, but found him “scornful of any suggestion that he had confessed to more murders”. Police nevertheless decided to resume their search of Saddleworth Moor, once more using the photographs taken by Brady and Hindley to help them identify possible burial sites. In November 1986, Keith Bennett’s mother Winnie Johnson wrote a letter to Hindley begging to know what had happened to her son, a letter that Hindley seemed to be “genuinely moved” by. It ended:

I am a simple woman, I work in the kitchens of Christie’s Hospital. It has taken me five weeks labour to write this letter because it is so important to me that it is understood by you for what it is, a plea for help. Please, Miss Hindley, help me.

Police visited Hindley, then being held in Cookham Wood, Kent, a few days after she had received the letter, and although she refused to admit any involvement in the killings, she agreed to help by looking at photographs and maps to try to identify spots that she had visited with Brady. She showed particular interest in photographs of the area around Hollin Brown Knoll and Shiny Brook, but said that it was impossible to be sure of the locations without visiting the moor. The security considerations for such a visit were significant; there were threats made against her should she visit the moors, but Home Secretary Douglas Hurd agreed with Topping that it would be worth the risk.Writing in 1989, Topping said that he felt “quite cynical” about Hindley’s motivation in helping the police. Although the letter from Winnie Johnson may have played a part, he believed that Hindley’s real concern was that, knowing of Brady’s “precarious” mental state, she was afraid that he might decide to co-operate with the police, and wanted to make certain that she, and not Brady, was the one to gain whatever benefit there may have been in terms of public approval.

On 16 December 1986, Hindley made the first of two visits to assist the police search of Saddleworth Moor. Four police cars left Cookham Wood at 4:30 am. At about the same time, police closed all roads onto the moor, which was patrolled by 200 officers, 40 of them armed. Hindley and her solicitor arrived by helicopter from an airfield near Maidstone, then she was driven, and walked, around the area. It was difficult for Hindley to make a connection between her memories of the area and what she saw on the day, and she was apparently nervous of the helicopters flying overhead. At 3:00 pm she was returned to the helicopter, and taken back to Cookham Wood. Topping was criticised by the press, who described the visit as a “fiasco”, a “publicity stunt”, and a “mindless waste of money”. He was forced to defend the visit, pointing out its benefits:

‘We had taken the view that we needed a thorough systematic search of the moor … It would never have been possible to carry out such a search in private.’

On 19 December, David Smith, then 38, also returned to the moor. He spent about four hours helping police pinpoint areas where he thought more bodies might be buried.Topping continued to visit Hindley in prison, along with her solicitor Michael Fisher and her spiritual counsellor, Peter Timms, who had been a prison governor before becoming a Methodist minister. She made a formal confession to police on 10 February 1987, admitting her involvement in all five murders, but news of her confession was not made public for more than a month. The tape recording of her statement was over 17 hours long; Topping described it as a “very well worked out performance in which, I believe, she told me just as much as she wanted me to know, and no more”. He added that he “was struck by the fact that she was never there when the killings took place. She was in the car, over the brow of the hill, in the bathroom and even, in the case of the Evans murder, in the kitchen”. Topping concluded that he felt he “had witnessed a great performance rather than a genuine confession”.

Brady and Hindley

During the 1987 search for Pauline Reade and Keith Bennett, Hindley recalled that she had seen the rocks of Hollin Brown Knoll silhouetted against the night sky.

Police visited Brady in prison again and told him of Hindley’s confession, which at first he refused to believe. Once presented with some of the details that Hindley had provided of Pauline Reade’s abduction, Brady decided that he too was prepared to confess, but on one condition: that immediately afterwards he be given the means to commit suicide, a request with which it was impossible for the authorities to comply.

At about the same time, Winnie Johnson sent Hindley another letter, again pleading with her to assist the police in finding the body of her son Keith. In the letter, Johnson was sympathetic to Hindley over the criticism surrounding her first visit. Hindley, who had not replied to the first letter, responded by thanking Johnson for both letters, explaining that her decision not to reply to the first resulted from the negative publicity that surrounded it. She claimed that, had Johnson written to her 14 years earlier, she would have confessed and helped the police. She also paid tribute to Topping, and thanked Johnson for her sincerity. Hindley made her second visit to the moor in March 1987. This time, the level of security surrounding her visit was considerably higher. She stayed overnight in Manchester, at the flat of the police chief in charge of GMP training, and visited the moor twice. She confirmed to police that the two areas in which they were concentrating their search—Hollin Brown Knoll and Hoe Grain—were correct, although she was unable to locate either of the graves. She later remembered that as Pauline Reade was being buried she had been sitting next to her on a patch of grass and could see the rocks of Hollin Brown Knoll silhouetted against the night sky.

In April 1987, news of Hindley’s confession became public. Amidst strong media interest Lord Longford pleaded for her release, writing that her continuing detention to satisfy “mob emotion” was not right. Fisher persuaded Hindley to release a public statement, in which she explained her reasons for denying her complicity in the murders, her religious experiences in prison, the letter from Johnson, and that she saw no possibility of release. She also exonerated David Smith from any part in the murders, except that of Edward Evans.

Over the next few months interest in the search waned, but Hindley’s clue had directed the police to focus their efforts on a specific area. On the afternoon of 1 July 1987, after more than 100 days of searching, they found a body buried 3 feet (0.9 m) below the surface, only 100 yards (90 m) from the place where Lesley Ann Downey had been found. Brady had been co-operating with the police for some time, and when news reached him that Reade’s body had been discovered he made a formal confession to Topping. He also issued a statement to the press, through his solicitor, saying that he too was prepared to help the police in their search. Brady was taken to the moor on 3 July, but he seemed to lose his bearings, blaming changes that had taken place in the intervening years, and the search was called off at 3:00 pm, by which time a large crowd of press and television reporters had gathered on the moor.

Topping refused to allow Brady a second visit to the moors, and a few days after his visit Brady wrote a letter to BBC television reporter Peter Gould, giving some sketchy details of five additional murders that he claimed to have carried out. Brady refused to identify his alleged victims, and the police failed to discover any unsolved crimes matching the few details that he supplied. Hindley told Topping that she knew nothing of these killings.

Ian Brady

Hoe Grain leading to Shiny Brook, the area in which police believe Bennett’s undiscovered body is buried.

On 24 August 1987, police called off their search of Saddleworth Moor, despite not having found Keith Bennett’s body. Brady was taken to the moor for a second time on 1 December, but he was once again unable to locate the burial site. Earlier that month, the BBC had received a letter from Ian Brady, in which he claimed that he had committed a further five murders – including a man in the Picadilly area of Manchester, another victim on Saddleworth Moor, two more victims in Scotland, and a woman whose body he allegedly dumped in a canal at a location which he declined to identify. The police decided that there was insufficient evidence from this letter to launch an official investigation.

Ian Brady, who went on hunger strike, pictured looking drawn and gaunt

Although Brady and Hindley had confessed to the murders of Pauline Reade and Keith Bennett, the (DPP) decided that nothing would be gained by a further trial; as both were already serving life sentences no further punishment could be inflicted.

Keith Bennett

In 2003, the police launched Operation Maida, and again searched the moor for the body of Keith Bennett. They read statements from Brady and Hindley, and also studied photographs taken by the pair. Their search was aided by the use of sophisticated modern equipment, including a US satellite used to look for evidence of soil movement. The BBC reported on 1 July 2009 that Greater Manchester Police had officially given up the search for Keith Bennett, saying that “only a major scientific breakthrough or fresh evidence would see the hunt for his body restart”. Detectives were also reported as saying that they would never again give Brady the attention or the thrill of leading another fruitless search on the moor where they believe Keith Bennett’s remains are buried. Donations from members of the public funded a search of the moor for Bennett’s body by volunteers from a Welsh search and rescue team that began in March 2010. In August 2012, it was claimed that Brady may have given details of the location of Keith Bennett’s body to one of his visitors. A woman was subsequently arrested on suspicion of preventing the burial of a body without lawful excuse, but a few months later the CPS announced that there was insufficient evidence to press charges. Keith Bennett’s body remains undiscovered as of 2019, although his family continues to search the moor.